Unpublished letters detail famed soprano’s painful relationships with husband, mother and Aristotle Onassis

Her mother blackmailed her, her husband Giovanni Battista Meneghini stole from her, and shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis was violent and abandoned her for Jackie Kennedy. Soprano Maria Callas was adored by audiences worldwide but she never knew real love offstage, and her life was even more tragic than previously realised, according to research.

In writing a new biography, Lyndsy Spence was given access to Callas’s previously unpublished correspondence and other material, which casts light on the torment of her marriage, the abuse to which Onassis subjected her and sexual harassment by the director of one of the world’s foremost conservatoires.

Spence said that the letters relating to Onassis reveal the terrifying ordeal she suffered, especially when, in 1966, his physical violence threatened her life: “There is also disturbing information from the diary of one of her close friends detailing how Onassis drugged her, mostly for sexual reasons – today we would class that as date rape.”

Writing to her secretary, Callas confided: “I wouldn’t want him [Onassis] to phone me and start again torturing me.”

On the pain of her marriage to Meneghini, Callas despaired: “My husband is still pestering me after having robbed me of more than half my money by putting everything in his name since we were married … I was a fool … to trust him.” She described him as “a louse”, lamenting that he “passes for a millionaire when he hasn’t got a dime”.

One letter refers to the then president of the Juilliard School of music in New York, a married man, turning the faculty against her and stopping her coming back for another term after she rejected his advances. She wrote to her godfather: “Peter Mennin fell in love with me. So, naturally, as I did not feel so towards him, he is against me.”

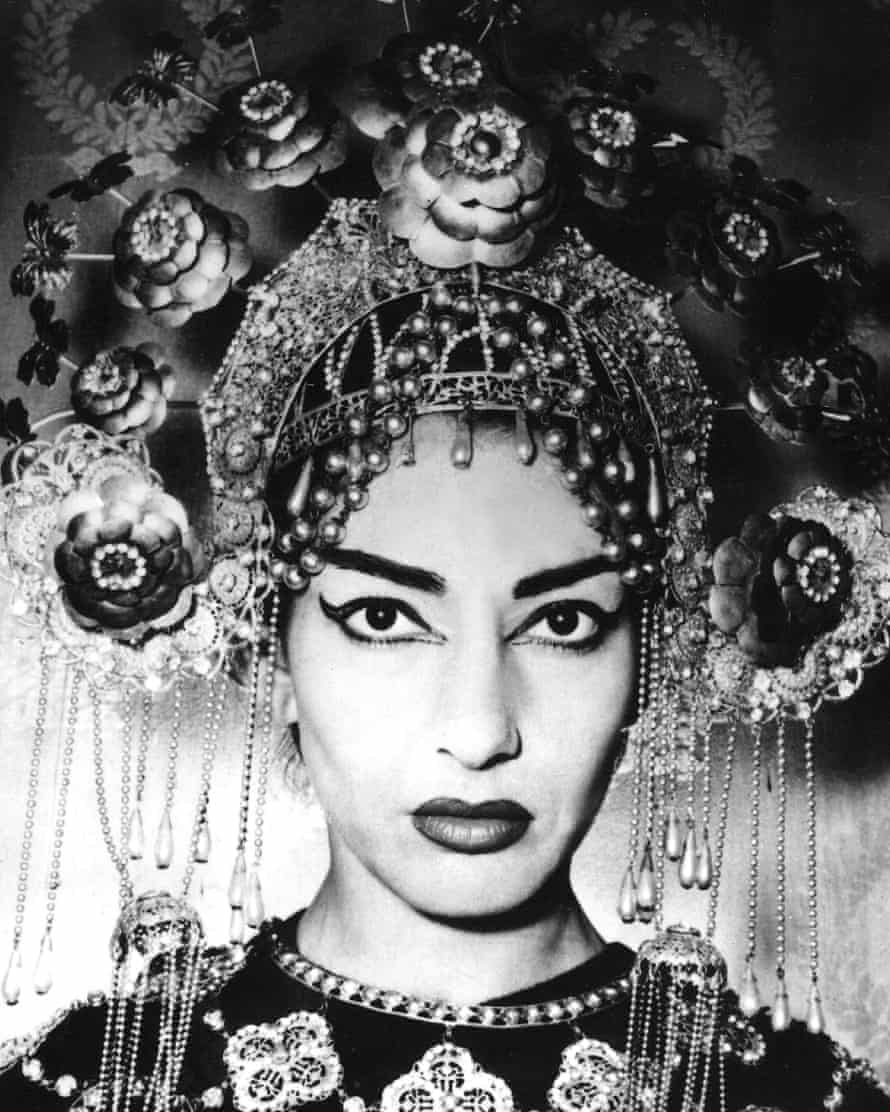

Callas, who was born in New York to impoverished Greek immigrants in 1923, was one of opera’s most revered singers. Her performances of Tosca at Covent Garden have been described as among the greatest opera experiences of all time.

Spence said: “I was given access to three enormous collections which were bequeathed to various archives in 2019 and, until now, have never been published. Among the papers were Callas’s letters revealing her innermost thoughts.”

The new revelations include the truth about Callas’s harrowing childhood in Europe. “Callas resented her mother, who worked as a prostitute during the war, for trying to pimp her out to Nazi soldiers,” said Spence.

Later, Callas’s mother sold stories to the press and blackmailed her to keep her mouth shut, writing to her daughter: “You know what cinema artists of humble origins do as soon as they become rich? In the first month they spend their first money to make a home for their parents and spoil them with luxuries… What have you got to say, Maria?”

Callas confided: “If she was a real mother to me a long while ago, I would [have] cherished her.”

Nor was her father better, Spence said: “He wrote her a letter, pretending he was dying in a pauper’s hospital in an attempt to get money from her. In fact, he had a minor ailment.”

Callas wrote: “I am fed up with my parents’ egoism and indifference toward me … I want no more relationship. I hope the newspapers don’t catch on. Then I’ll really curse the moment I had any parents at all.”

The material also casts light on her great soprano rival, Renata Tebaldi, whom she had denigrated in likening their respective voices to champagne and Coca-Cola, while Tebaldi had accused Callas of lacking a heart. But they each dismissed their prima donna duel of the 1950s as a myth made up by the media. Callas insisted that she had actually said cognac not Coca-Cola, telling one interviewer that she wished she had Tebaldi’s voice, and Tebaldi described Callas’s voice as “the best”.

Now denials of their feud are contradicted by a previously unpublished letter in which Callas wrote of Tebaldi: “She’s as nasty and as sly as they come.”

That same letter, dated 1957, reveals that the American-Greek’s loathing for the Italian singer led to Callas accusing her of finding fame through “being my rival” and of using Tebaldi’s mother’s reported heart attack to further her career in cancelling her appearance at the Metropolitan Opera. Callas wrote: “Her mother had nothing special wrong with her. Not even a heart attack … Do you think it’s publicity or maybe Renata did not feel well and [maybe] her mother had the flu and that was a perfect excuse for her not singing… and to have a triumphant poor Renata on her first performance.”

She continued: “I’m surely fed up with all this nauseating poor Renata business … God does not like such methods for publicity and weapons against me.”

Callas died in 1977 aged 53. The unpublished material also gives new insights into her health problems, which affected her performances in the 1960s, and her dependence on drugs. She lost her voice several times.

Spence said: “I tracked down the neurologist who treated her before her death. Callas suffered from a neuromuscular disorder whose symptoms began in the 1950s, but she was dismissed by doctors as ‘crazy’. It also explains the loss of her singing voice, which cut her career short.

“The death of Callas is a harrowing tale. Alone in her Parisian apartment, she relied on her estranged sister, Jackie, and companion, Vasso Devetzi, to supply her with [a sedative]. Her life was full of tragedy, but I wanted to give her her voice.”

Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas by Lyndsy Spence is published by The History Press on 1 June

Fonte da Publicação: https://www.theguardian.com/

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário